Insights into how neurons in the brain respond to injury could lead to new ways of treating stroke and dementia due to cancer radiation according to two papers being published in Nature Medicine.

Using a rat model in which stroke was induced by temporarily blocking arterial flow to the brain, Andreas Arvidsson and colleagues at Lund University Hospital show that the damaged area-akin to human stroke-is infiltrated by new neurons. It appears that new neurons are produced in a different area of the brain called the subventricular zone and travel to the site of injury. Once there, the neurons take on the characteristics of the neurons that were destroyed.

The problem is that only 0.2%, or 1,600 neurons, of the damaged neurons are replaced. However, now that it has been shown that the brain makes a natural effort to repair itself following stroke, finding a way of augmenting this re-growth may offer new therapies for the debilitating and potentially lethal condition.

In a separate paper, Theo Palmer and colleagues from Stanford University have discovered why all patients that undergo radiation therapy for brain, and head and neck cancer inevitably suffer from cognitive decline.

Using a rat model, Palmer's group found that radiation exposure drastically reduces the regenerative abilities of neurons in the hippocampus-a brain region involved in learning, memory and spatial awareness. Specifically, the scientists believe that radiation affects the stem cell pool that gives rise to new hippocampal neurons. Future treatment should therefore be aimed at protecting, or replacing these stem cells during radiation treatment for such cancers.

WHY WAS THE 1997 HONG KONG FLU SO DEADLY?

Influenza is a disease caused by one of three strains of virus, A, B or C. Type A is usually responsible for the large outbreaks and is a constantly changing virus. The worst outbreak was the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic, which killed around 30 million people worldwide. Although waves of influenza virus have threatened the human population since then--Type A and B influenza lead to 20,000 deaths and over 100,000 hospitalizations each year in the US--fortunately none has been so deadly.

However, in 1997 epidemiologists and public health officials got their first glimpse of an entirely new variety of human influenza, subtype H5N1, a strain that had only ever previously been observed in birds and which struck in Hong Kong. Although there were 18 human infections and six deaths, slaughtering the city's 3 million chickens stopped the outbreak in its tracks.

Learning to identify a particularly virulent strain of influenza virus as soon as it appears should help to avert catastrophe. Scientists lead by flu expert, Robert Webster of St June's Research Hospital, Tennessee, have now characterized the gene that made the Hong Kong H5N1 virus so deadly. Webster's team has shown that the H5N1 virus is highly adept at escaping the body's natural antiviral defenses, namely cytokines such as interferon and TNF-alpha. A protein produced by influenza viruses called NS1 (nonstructural 1) enables them to disarm the body's interferon system, and the scientists found that H5N1 carries a mutation at position 92 of the NS1 gene that makes it a particularly deadly form of influenza.

Now that we know what makes the H5N1 strain of flu especially deadly, continuous surveillance of virus types and the design of an effective vaccine can help avoid another epidemic.

Ultimi Articoli

Strapazzami di coccole Topo Gigio il Musical: una fiaba che parla al cuore

Goldoni al Teatro San Babila di Milano con La Locandiera

Ceresio in Giallo chiude con 637 opere: giallo, thriller e noir dall'Italia all'estero

Milano celebra Leonardo — al Castello Sforzesco tre iniziative speciali per le Olimpiadi 2026

Trasporto ferroviario lombardo: 780.000 corse e 205 milioni di passeggeri nel 2025

Piazza Missori accoglie la Tenda Gialla – Tre giorni di volontariato under zero con i Ministri di Scientology

Neve in pianura tra venerdì 23 e domenica 25 gennaio — cosa è realmente atteso al Nord Italia

Se ne va Valentino, l'ultimo imperatore della moda mondiale

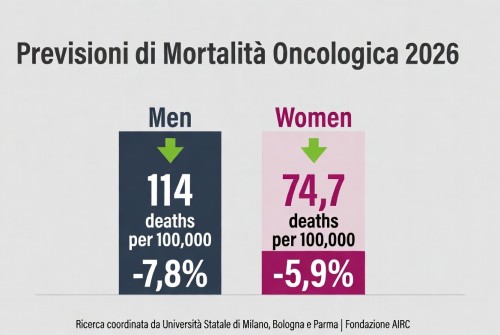

La mortalità per cancro cala in Europa – tassi in diminuzione nel 2026, ma persistono disparità